Porosities: Ethnographic Salon 2023

April 20, 2023

USC Doheny Memorial Library and over Zoom

Eleana Kim (UC Irvine), Gabriela Soto Laveaga (Harvard University), and Teresa Montoya (University of Chicago)

The 2023 Ethnographic Salon took place on April 20th at the USC Doheny Memorial Library and over Zoom. You can find a full recording of the event on our YouTube channel.

Drawing on our work with the Infrastructures of Ethnography initiative, we explored the theme of POROSITIES. We were joined by three fantastic guests: Eleana Kim (UC Irvine), Gabriela Soto Laveaga (Harvard University), and Teresa Montoya (University of Chicago).

Porous formations are filled with emptied-out spaces. Porous worlds require meanderings and intricate forms of roaming. Analytic and political moves in porous substrates demand attention to both full and empty space. In porous conditions, interstices require forms of sensing that denaturalize the value of visibility as necessary or empowering. In these interstices, we need to ask who is entitled to or forced to remain hidden, covert, or secluded. Privileging porosity invites explorations of how fluid conditions and movement-based ways of life are turned into “states” of crisis, of emergency, of shock.

Students and ES collaborators explored the concept of porosities within their individual research projects. Below are selections from their porous ponderings, with links to their full projects.

Selections from students’ submissions

Grace Simbulan, USC

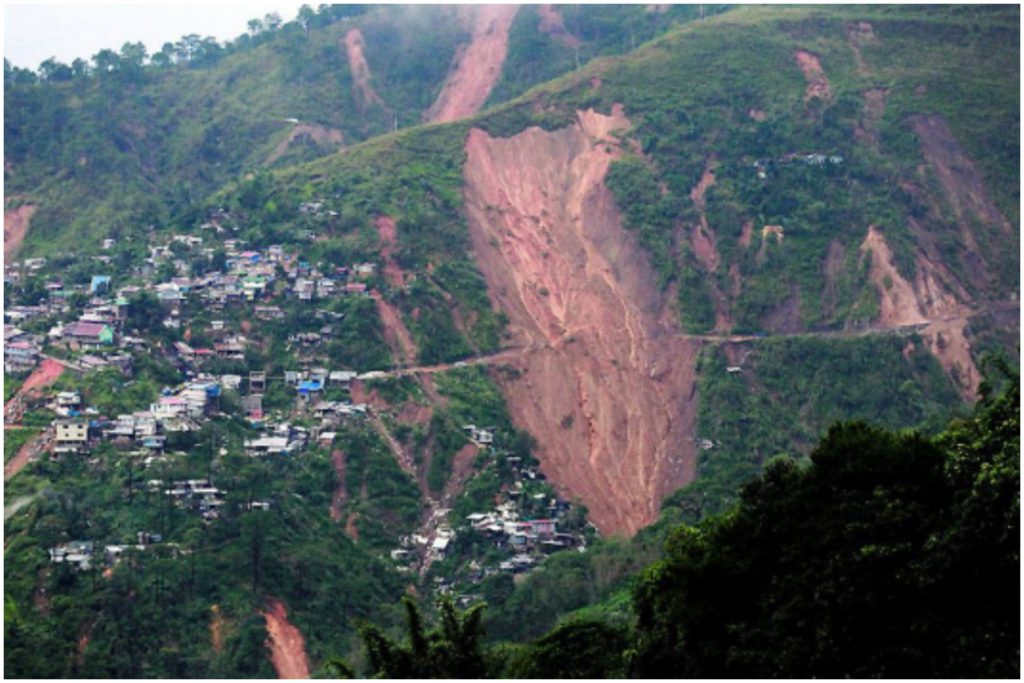

Precarious Living on Porous Lands

How are spaces and forms of life in mining communities in Benguet hollowed out? My research focuses on miners, both small and large scale, in two mining communities in the province of Benguet, Philippines. My primary objective for this initial stage of my research was to examine hollowed out spaces (i.e., mountains, bodies, relationships, luck). I approach hollowed-out spaces in a similar fashion to how Macarena Gómez-Barris examines microspaces or zones of catastrophe in extractive zones. She defines extractive zones as spaces “traversed by colonialism and extractive capitalism” (Gómez-Barris, 2017: p, 2), which continue to leave a deep imprint in these geographies. Instead of equating the act of hollowing out to emptying, that focuses solely on the colonial conditions of these spaces, I suggest that we pay close attention to the microspaces within these extractive zones and highlight submerged perspectives to challenge the totalizing view of “no future”, defined as the inevitability of the anthropogenic-led collapse of the planet and its ecologies (Gómez-Barris, 2017).

For this project, I constructed a maze-like piece using ropes, cork tiles and other materials. I used ropes to form the walls of the piece and the entire piece is covered with grass-like materials in different hues of green. Despite appearing to be an empty space, the maze is actually filled with assorted objects concealed beneath patches of grass-like materials. These objects include elements found in the mines and male figures covered in transcripts of interviews with my interlocutors. The piece illustrates how hollowed out spaces are neither empty nor meaningless. By closely examining these spaces, one can uncover a multitude of lively engagements, encounters, and relationships not only between miners but also between human and non-human beings that inhabit these mountains. Read more about Grace’s project.

Read an update on Grace’s project, written after fieldwork during summer 2023, and check out a short video of her work so far.

Brodie Quinn, USC

SLAB CITY: ADAPTING TO A POROUS BORDER

How is community cohesion maintained and a homeplace constructed when the borders of Slab City are so porous? My project looks at the off-the-grid encampment in the Southern California desert called “Slab City.” This is a place that residents call “the last free place in America,” a place where a community of squatters, artists, migrants, survivalists, digital nomads, travelers, and retirees call home—some for the entirety of the year, most others only in the winter months. Slab City is “unofficial” in many ways: there is no official electricity, law enforcement, taxation, or governance. What was once Camp Dunlap, a military training camp, is now a place where people come and go, make community, and try to find freedom, however they imagine that to be. The borders of this community are more porous than others; without land ownership and oversight, people are free to come and go, and many do. The porousness of the community border is something highly valued by this community, contributing to their ideas of freedom and alternative lifestyle—an important and visible contrast from what they call “Babylon,” that is, the stationary, capitalistic, private property-owning society outside the 1-mile square area of Slab City.

For this research, I wanted to know how a community can be maintained when the border here is a place of constant, unpatrolled flow. And I wanted to know how a sense of place is constructed in this desert where people value, perhaps more than anything else, this freedom of movement. Read more about Brodie’s project.

Read an update on Brodie’s project, written after fieldwork during summer 2023.

Toh Sook Lin Toh, USC

THE POROUS BLACK-BOX IN COMPUTER SCIENCE

This piece reflects some considerations developed over a short-term fieldwork project studying Computer Science (CS) graduate students enrolled at USC. This project began with the intention to investigate the ‘black-box algorithm’ by examining pedagogical practices at a graduate level, but soon became an observation of how CS students are trained to understand data processing and use tools and frameworks in Web Technologies and AI that do not necessarily fall under the formal ‘black-box’ portion of CS (limited mostly to machine learning). Machine learning, and particularly deep learning, came up a lot in conversation, especially because of the hype around ChatGPT. Often considered the most complex and advanced part of CS – and the part gaining the most mainstream attention – my interlocutors would downplay the complexity of other areas in CS in comparison to the black-box of machine learning.

I have used the metaphor of a ‘porous material’ to begin thinking about how data gets transformed and the trial-and-error processing in coding. Using porosities specifically for models not considered black-box helps to complicate the self-evident, straightforward nature of these processes, by highlighting the blockages and ‘half’ transparencies. “All of this might seem like a black-box to other people, but it’s not to us”. From an outside perspective, the immateriality of code provokes assumptions about opacity, and for the programmer, it is transparent in contrast to the unexplainable black-box machine learning model. So rather than rely on this binary, if we think of the process as porous, we can imagine a way of ‘seeing’ that involves adjusting and removing certain ‘blockages’ to create holes that can help put together a mental image of the output. This sometimes methodological, sometimes menial and random method of debugging can be interpreted not just as a way of ‘fixing the code’ but a way of seeing and understanding. Read more about Sook Lin’s project.

Read an update on Sook Lin’s project, written after fieldwork during summer 2023.

Rachel Howard, University of Chicago

DAMS AS ETHNOGRAPHIC INFLECTION POINTS: AFFORDANCES AND FORECLOSURES

In my fieldwork practice, I have worked towards attuning to ethnographic inflection points: I have understood these points as moments of pause or whiplash that create or allow for ruptures in narratives or time. There are other ways to consider inflection points. One way to think of an inflection point is via Roland Barthes’ notion of the “punctum” in a still photograph: “a sting, speck, cut, little hole…an accident which pricks me (and also bruises me, is poignant to me” (1980:27). Another way to think of an inflection point is the subject “you” or “I” in a dialogue—these changes meaning depending on who is speaking, what Michael Silverstein (1976) would call “deixis”. Another way to think of an inflection point is as the suffix “-ed” in English, which changes the temporal outlook (tense) of an activity or a verb.

For this project, I untangle [ethnographic] from [inflection point] in order to explore how and why these are generated. Anthropologists do not simply mechanically acclimate to their social—and otherwise—environments. Instead, I ask: what is afforded us when we consider the routes that our attention takes, and where it is held? In conducting research on water systems in Phoenix, Arizona, I take the dam as the generator of inflection point—and the system it creates and the ruptures in time and space it affords as a space of unfolding, an ethnographic problem-space. Read more about Rachel’s project.

Katie Ulrich, Rice University

CLICK TO TRANSFORM SUGARCANE

My research is with scientists and industry actors in São Paulo, Brazil who research how to make biofuels and other renewable bioproducts, like bioplastics, from sugarcane. Since the beginning of this project, I have circled around the core question of how these actors transform sugarcane from a crop with a dark history into the basis for new sustainable futures. How does this happen as/in addition to/alongside the molecular transformation of sugarcane juice into biofuels and bioplastic? This led to the methodological question of how to trace such transformations. One of the methods I developed to do so is called the “sugar library.” I cataloged various “forms” of sugarcane, capaciously conceived, that I encountered in the field. This included images of cane I came across, photos I took of cane in various places, stories people told me about the plant, their decades-old memories of it, broader discourses I heard about its history or politics, poems and artwork about sugarcane, knowledge artifacts like metrics and charts, and even absences and gaps when I thought sugarcane would’ve been brought up or present.

By tracing different forms of sugar(cane), I was able to start to see how different forms related to each other and became each other—how various transformations were unfolding. Yet what I came to learn that I wasn’t expecting was that there were different forms of transformations. There are not simply many different things that sugarcane can transform into and transform from, but several qualitatively different modalities of such transformation. These different modalities, or genres even, had their own patterns of materials, relations, practices, people, sites, and embodied theories of change. Thinking with the concept of porosities led me to wonder if these modalities or genres of transformation are porous with each other, or overlapping, or something else.

Explore the interactive sugarcane map on Miro.

Eduardo Romero Dhanderas, USC POSTDOC

MASTERING DENSITY: THE TRANSDUCTIVE EFFECTS OF TIMBER BUOYANCY IN PERU’S TROPICAL TIMBER SUPPLY CHAINS

As an ethnographic concept, porosity can be approached in metaphoric terms as a relational property of experience that allows us to spatialize the unexpected interstices and gaps that are immanent to any regime of power and knowledge. But in many circumstances, it is also politically productive to think about it literally, as the material condition from which certain techniques, relations and circulations can be cultivated in relation to objects characterized by heterogeneous distributions and concentrations of matter. Taking porosity as a guiding concept for ethnographic inquiry can thus bring us into a recognition of the political and economic effects of the internal nonhomogeneity of various materialities, and how subtle differentials in the microscopic structure of matter can significantly affect not only what can be done to a body, and also how the properties of bodies can reverberate across vast economic and political processes of circulation and transformation.

In this brief textual companion to my video, I draw on my long-term fieldwork in Peru’s Amazonian region of Loreto in order to consider how the disparate concentrations of wooden matter within different species of trees have inflected the course of Loreto’s tropical logging industry over the last few decades. I contend that the density of wood, the given ratio of wooden mass to volume in a particular wooden body, constitutes a transductive force that has historically conditioned the rhythms, frictions and crafts involved in the labor of harvesting and transporting logs out of the rainforest and into the regional sawmills where timber is to be processed. If transduction is the process by which a signal can move from one domain to the other, producing analogous variations across heterogeneous mediums, I suggest that the density of wood in Loreto’s tropical logging industry constitutes a transductive reverberating force through which microscopic distributions of wooden matter can make themselves felt across time and space, from the intimate bodily attunements cultivated by loggers spurring timber out of the rainforest, to the historical cycles of contraction and expansion of Peru’s tropical timber supply chains. Read more about Eduardo’s project.